Ship of Tolerance, London, England; September 17, 2019

Ship of Tolerance, London, England; September 17, 2019

When I tell Americans that my grandmother is British, they usually say something like “Oh so when you visit her, you drink tea and hang out in castles?” No, she prefers coffee and — hmm. We do actually spend a lot of our time together at castles or palaces or other “stately homes,” as big country mansions are called in the UK, because we go to National Trust and English Heritage properties on day trips. This past spring, we even ended up at a giant house that looked a little familiar to me, and my grandmother casually remarked that I’d been before, for her and my grandfather’s 40th anniversary party. Because of course she had an anniversary party at a 12th-century palace.

Hartlebury Castle was built in the 13th century, and from the start was the seat of power for whoever was Bishop of Worcester at the time. Various royals have visited over the years — Mary Tudor stayed there instead of nearby Ludlow because Ludlow had the plague (a serious vacation downer); King George III and Queen Charlotte took a walk in the gardens in front of 8,000 people (what a strange zoo); and Queen Elizabeth II planted a tree here once (it’s still there). But the best royal story is when Bishop Hurd renovated an entire bedroom for the Prince of Wales to stay in, only for the prince to leave after less than an hour. Rude!

That same Bishop Hurd built a library renowned for holding many works from the Age of Enlightenment. Today, it is the only Anglican bishop’s book collection housed in the same room and shelves built for it. The photos on the website look beautiful, but when we visited, it wasn’t on one of the days the library is open to the public, so I’ll content myself with my grandmother’s memory of having cocktails there during some fancy event a few decades ago. She said it is indeed a lovely room. So there you go.

Why has my grandmother been a fairly frequent visitor of this mansion? She’s very involved with her church, and has known the last 6 bishops of Worcester through her work with the diocese. In fact, she and my grandfather were a part of the history of the palace. In the 80s/90s, my grandfather, as Chairman of the Board of Finance for the Diocese of Worcester, was tasked with finding an artist to paint Bishop Philip Goodrich’s portrait. He had decided on someone, but hadn’t yet asked him to do the job, when my grandmother said, “Dear, you’ll have to find someone else to do it. I’ve just seen the obituaries…” So the two of them drove to London and spoke with a curator in the National Portrait Gallery. They recommended an artist who’s most well known for her sculptures but does many paintings as well, Maggi Hambling. Later, once the painting was completed, they drove back to London to ferry the official portrait back to Worcestershire. The portrait tends to polarize people; I’m one of the ones who likes it, but apparently some people think it doesn’t capture Bishop Goodrich’s warmth. What do you think?

The final part of the castle is the Worcestershire County Museum, which holds a large toy gallery (including a large map of fairyland drawn by an artist according to instructions from his children), a Victorian school room, clothes from various decades, and even a display of archaeological finds, including a mammoth’s tusk! I especially liked the large display of gypsy caravans, with their bright colors and sometimes ornate carvings. The display plaques made an effort to dispel some of the racist stereotypes still repeated about travelers; dispiriting that people need a museum to remind them that others are fellow humans deserving of respect.

Stately homes nowadays are always trying to make accessible the lives of the people who used to live there, so that visitors can feel more of a connection with the place. I like the places that try to do this across class lines — introducing visitors to parlor maids as well as ladies of the house — and the ones that ambitiously try to show the changes in a house over the hundreds of years of its existence. I think it’s just what a national property open to the public should attempt, making history feel real and immediate. But history doesn’t have to be ancient; it can be much more recent than that. And different histories layer themselves on top of one another (one of my favorite themes). Going to Hartlebury with my grandmother layered the histories of the palace for me: a 1980s cocktail party in the 18th-century library; a 1990s celebratory dinner in the great hall that has held feasts since its construction in the 13th century; and a line of paintings going back hundreds of years, including one portrait driven down from London by the woman I was sharing tea with in the castle restaurant. Well, I had tea; she still prefers coffee.

From the Tools of Endearment series by Kalliopi Lemos, O2 Arena, London, England; July 13, 2018

Today, I took in:

Mary Gaitskill’s “The Girl on the Plane” in 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories

Anthea Hamilton’s performance art installation The Squash at the Tate Britain

I made:

a couple turns ’round my neighborhood park with a friend visiting from overseas

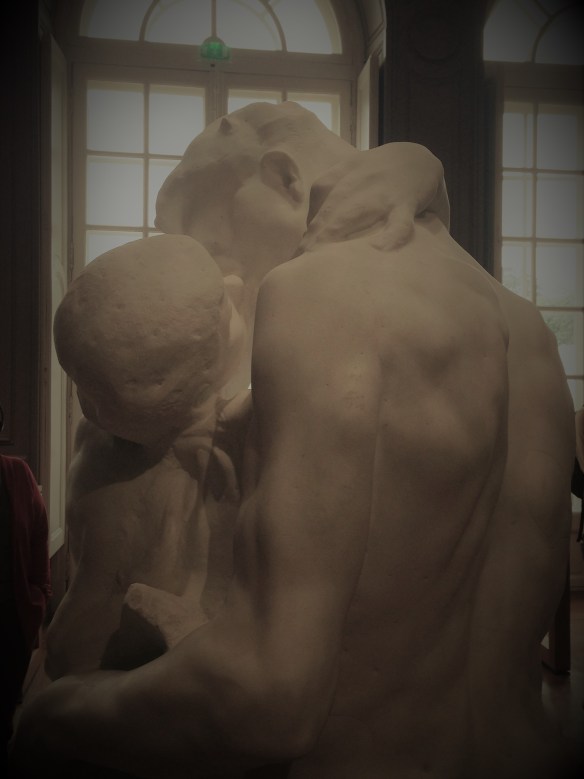

The Kiss, Rodin Museum, Paris, France; June 5, 2016

Today was so packed that I’m afraid I haven’t had time to write up anything new for this post, so let me point you back to another post on black artists that I really enjoyed writing and even more enjoyed researching: the Soul of a Nation exhibition at the Tate Modern from the autumn. It was one of the most challenging, upsetting, and thrilling art exhibitions I’ve been to in years. It highlighted artists from across the United States during the period of Black Power — Malcolm X, the Panthers, explicit resistance, self-protection, declarations of self-worth and ability, communal action. Black American visual artists from this time covered the spectrum from paintings to sculptures, abstract to meticulously detailed realist, purposely political to more personal explorations. Many of the issues of representation and artistic responsibility or freedom which were explored then resonate today. Take a look at the artists mentioned in that post and I’m sure you’ll find someone whose work speaks to you.

London Lumiere, London, England; January 19, 2018

Today, I took in:

the Basquiat exhibition “Boom for Real” at the Barbican, with friends — I hadn’t known much about Basquiat at all before I went, just sort of recognized a style; the exhibition is a good intro to this autodidact’s wonderfully sprawling range of interests and impressive commitment to creating

an episode of Miranda

Today, I made:

a little progress in Duolingo, even if I did have to repeat a section

London, England; July 8, 2017

If you’re in London in the next week, and you’ve not yet visited the Soul of a Nation exhibition at the Tate Modern, let this be encouragement to see it before it closes on the 22nd. If that’s not you, let this be a way to enjoy some excellent art. Content warning: some of these images are violent. Super important and well done, but potentially disturbing. Copyright note: I believe this falls within the Tate’s photography requirements of “personal use.”

The Soul of a Nation at the Tate Modern is one of the most challenging, upsetting, and thrilling art exhibitions I’ve been to in years. Before you even enter the exhibition space, you can watch snippets of speeches from five leaders of civil rights, Black Power, and liberation movements (Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Stokely Carmichael, and Angela Davis). You see Stokely responding to MLK and Malcolm X, James Baldwin teaching Europeans about American racism, Angela Davis taking a broad and pragmatic view of how the struggle fits in her life and she in it. This introduction to the exhibition is small but important. It situates us firmly within the black community in the United States in the 1960s and ’70s. We’re not hearing what white people thought about the issues or what approach white people thought black people should take; we’re hearing how black people had this discussion amongst themselves, and the myriad approaches they took to dismantling systemic racism and building a better world.

April 4 by Sam Gilliam

Once you enter the exhibition space, with the voices of cultural and political leaders still ringing in your ears, you immediately meet the artistic leaders. Let no one tell you that art and politics don’t interact: the Spiral artistic group was formed in direct reaction to the March on Washington in 1963, so members could discuss how to represent black folks in their art, and how to fight political battles in their art.

America the Beautiful by Norman Lewis

Processional by Norman Lewis (apologies for the slight blurriness)

My favorite thing about these two paintings by Norman Lewis is how they talk to one another. “America the Beautiful” on the left is a collection of white figures on a black background, which as you look more closely you see is a KKK rally, taking over the canvas and popping up almost randomly, like you never know where they’re lurking, intending harm. “Processional” on the right is a collection of white figures on a black background, which as you look more closely you see is an energetic crowd of people marching forward. It’s the Selma march, and as the museum placard suggested, the gradually widening scope of the view of figures is like a flashlight leading through the darkness. Two similarly simple approaches, two radically different results.

The next room cleverly combined art of the Black Panther group (mostly from their paper but also from posters they mass-produced to reach more people) and murals painted in black neighborhoods in cities across the United States — this room was “art on the streets,” art that was made to inspire and fire up. Some of the murals have fallen into disrepair, but I know I’ve seen some — or some like them — on the south side of Chicago, although I can’t recall if I’ve seen the Wall of Respect, one of the first murals to go up during this time.

Some of the stories behind the pieces I was familiar with, and others were new to me. I did not know about Fred Hampton — Black Panther activist shot to death in a raid by Cook County cops after being drugged by an FBI informant. I did not know that during his trial for conspiracy and inciting a riot as part of the Chicago Eight, Bobby Seale was ordered bound and gagged in the courtroom by the judge because the judge didn’t like his outbursts. (Also Seale’s later prison sentence was not for the original charges but for contempt charges the judge applied during that trial.) Archibald Motley, who painted “The First One Hundred Years” over a ten-year period, never painted again after he completed this work.

Other groups and collectives formed, including the Weusi collective, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, AfriCOBRA, Smokehouse Associates, and many others. A few of the rooms in this exhibition feature work from just one or two groups, so you can get a good sense of the general approach and what they focused on.

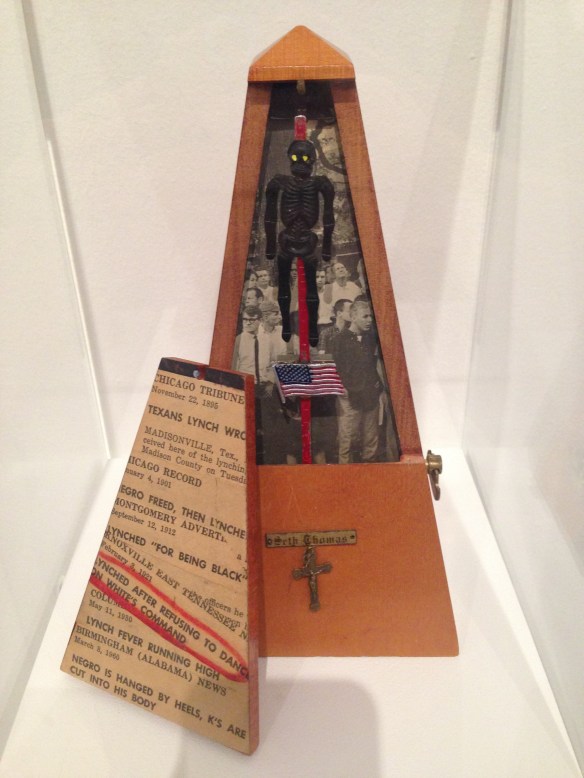

I Got Rhythm by Betye Saar

A room full of collage, sculpture, and found object art had some truly chilling pieces. Betye Saar’s work is deeply affecting — titles that seem carefree like “Sambo’s Banjo” and “I Got Rhythm” are attached to mixed-media punches to the gut. Each tiny item in each piece adds layers of meaning — the little crucifix at the bottom of a lynched man in “I Got Rhythm,” the toy gun nestled in the top of the banjo case so Sambo might have a chance of resisting and surviving in “Sambo’s Banjo.”

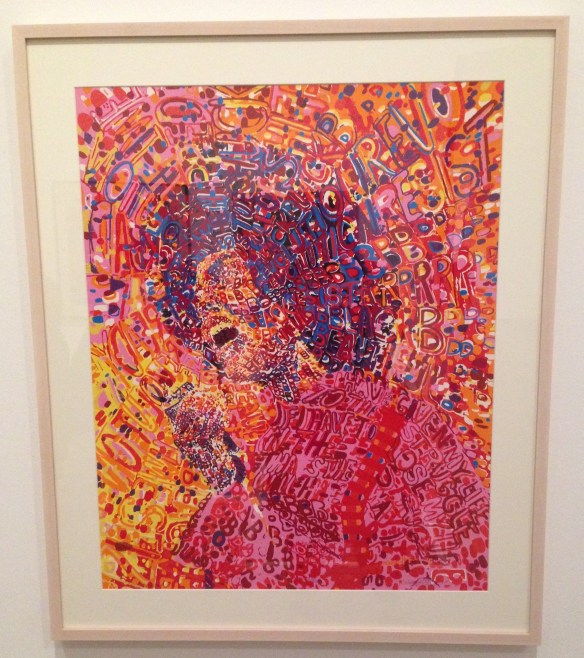

Revolutionary by Wadsworth Jarrell

Detail of Black Prince by Wadsworth Jarrell

Walking into the AfriCOBRA room midway through the exhibition was like walking into an air-conditioned building after walking for miles in summer heat, a relief. The AfriCOBRA manifesto was explicitly hopeful: they wanted an aesthetic of “rhythm,” “shine,” and “color that is free of rules and regulations.” They made works to lift people up, and they reprinted them for wide distribution, so that black people all over the country could be inspired by positive images of black folks. Which is not to say that this isn’t itself a challenge, because it certainly challenges the white supremacist myth that black people are inferior and not worth celebrating. And in fact most of the art was explicitly political as well, like the work by Gerald Williams reminding people “don’t be jivin” or Wadsworth Jarrell’s portrait of Angela Davis, made up of words from her speeches radiating from the center of the painting. Make no mistake, representation on your own terms is a powerful form of resistance.

One of the debates within the black artistic community at the time was whether abstract art could be considered part of the movement as a whole. Abstract artists argued that because the art was theirs, and they were black, it was therefore part of the political black art movement. It’s like improve in jazz, William T. Williams said, and then he painted Trane, named for John Coltrane, which I think is an excellent way to win an argument.

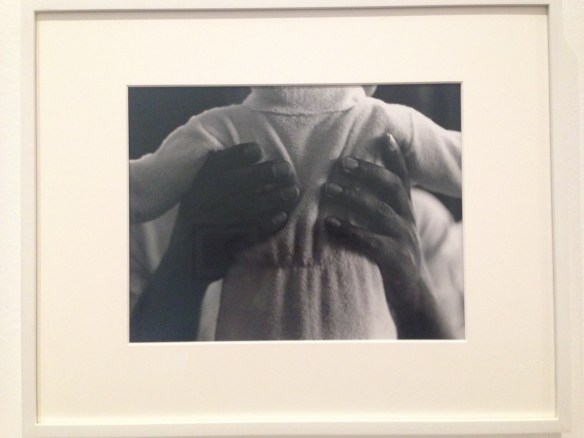

There was a room on photography and how different ways of developing film brought out different skin tones in the black subjects; there were connections to the wider Black Arts Movement and samples from poets who collaborated with visual artists; there were many reminders that one of the constant themes in black liberation movements of 50 years ago was an end to police brutality — for all those who want to talk about “how far we’ve come”; there was a Spotify playlist you could listen to on your headphones during your walk around the exhibition and which I listened to after, getting pumped up to Gil Scott Heron as I strode along the Thames. There was so much to see, read, and absorb. Much gratitude to the artists who fought the good fight and explored their own creativity during the 1963-1983 period explored here, and beyond.

Bill & Son by Roy DeCarava